History of the Fellsmere Garage and the Weigles

The Fellsmere Garage at 130 N. Broadway in Fellsmere was initially operated by Ellsworth Weigle after it was built in 1925.1 The garage was located just north of the Dixie Playhouse on the west side of North Broadway north of New York Avenue, northwest and across from the Fellsmere Inn. Ellsworth repaired vehicles at the 2,992 square foot garage for a period of 20 years before he sold the garage in 1945.2

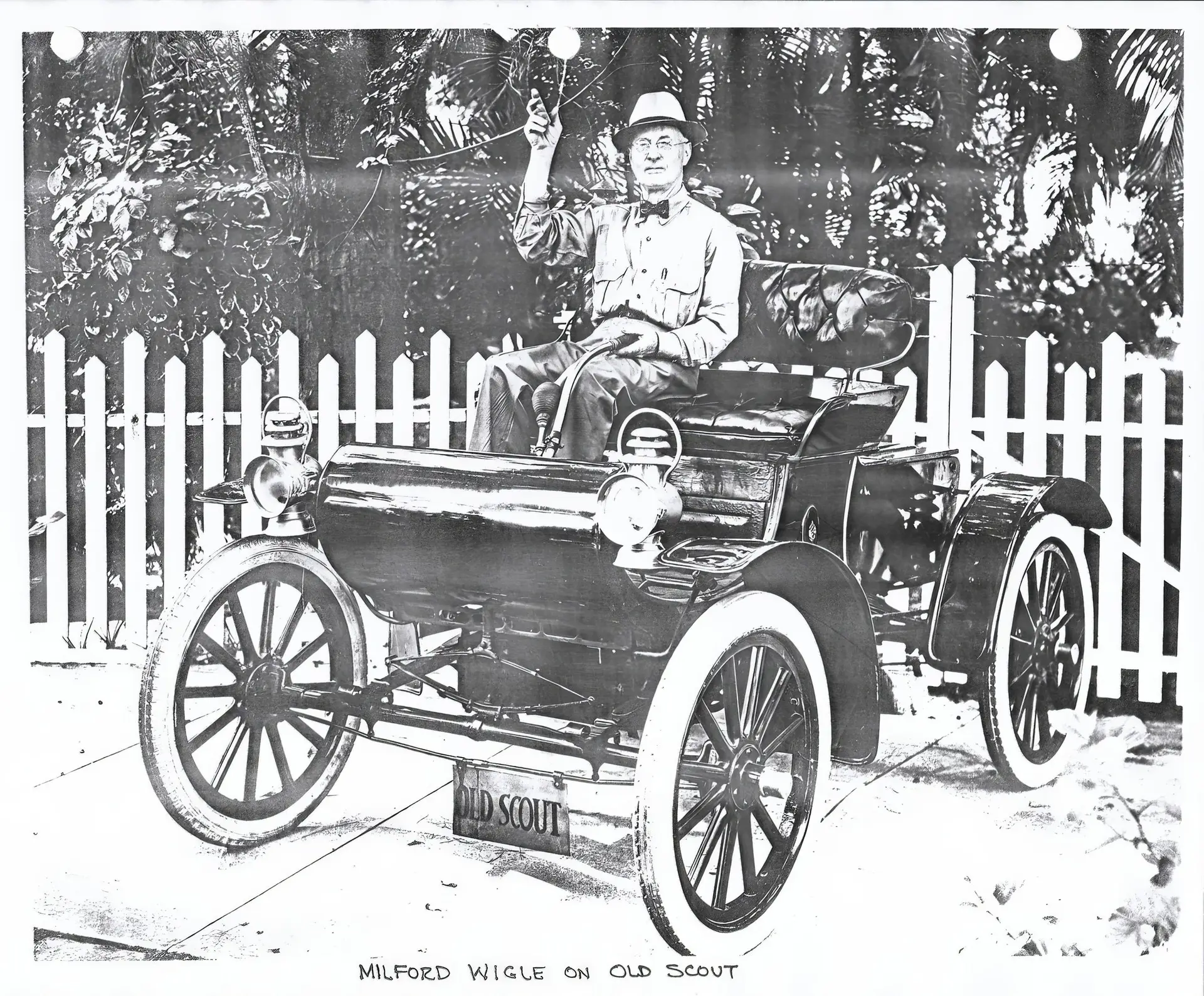

Ellsworth was the oldest son of Milford and Laura Weigle.3 Ellsworth’s father was nationally known and recognized as a famous mechanic in the early 1900s. Like his father, Ellsworth was also a mechanic. After a series of different jobs, Milford Weigle (father) became a test driver for the Olds Motor Works in Detroit, Michigan, in 1902.4 In 1905, three years later, he was selected as a mechanic/co-driver for driver Dwight Huss to race in an Olds Motor Works Oldsmobile Standard Runabout automobile from New York, New York, to Portland, Oregon, against another Oldsmobile automobile.5 This was the first transcontinental automobile race in the United States.6

The race started in New York City on May 8, 1905. Milford Weigle and Dwight Huss raced against Percy Megargel and Barton Staunchfield, approximately 3,500 miles across the country, in Oldsmobile runabouts. The race was initially estimated to take 30 days to complete. However, it took much longer than expected due to various factors including weather conditions that no one would be willing to drive through today.7 Most of the entire journey was on dirt and muddy roads but sometimes the cars had to drive in deep sand and over lava rocks. Fortunately, none of the four men involved in the race suffered any debilitating injuries, although Megargel and Staunchfield’s nearly drowned when their car fell through a wooden bridge in Nebraska. Also, while crossing the Cascade Mountains in Oregon, both men came within inches of losing their lives as their car slid down the mountain coming to a stop while hanging over a cliff.8

Weigle and Huss arrived in Portland, Oregon, 44 days after the start of the race to win on June 21, 1905. Megargel and Staunchfield got lost and showed up several days later. Weigle and Huss were greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of approximately 350,000 people who hailed them as instant celebrities after the grueling race across the country.9

After the race, Milford returned to his job at the Detroit Olds factory but moved to Lansing, Michigan, in August 1905.10 In June 1907, he beat the world’s record in a race with his “road machine” in Denver, Colorado. In 1909, Milford moved his family to Newcastle, Indiana, where he worked for the Briscoe Automobile Factory that made the “Maxwell” automobile.11

In March 1917, a cyclone hit Newcastle, Indiana, destroying many of the homes on the street where the Weigles lived. It was a terrible experience for the family.12 A friend of Milford’s who lived in Vero Beach, Florida, influenced the Weigles to move south to Fellsmere, Florida. Milford came to Fellsmere in December 1916, and his family arrived in April 1917.13

In 1920, Milford opened his own garage at his home on Ditch 8 (now 109th Street) near the Park Lateral.14 Milford, who had an excellent voice, became the choir director of the Fellsmere Methodist-Episcopal Church (now the Fellsmere Historical Church at 39 N. Broadway), and obtained the church bell in 1925, which is still rung today.15 He was also a member of the Fellsmere Masonic Lodge, which was responsible for laying the cornerstone of the Fellsmere Public School at 22 S. Orange St. (now Fellsmere City Hall) on January 31, 1916.16

Milford and his wife, Laura, moved to Ft. Myers, Florida, in 1929, where he worked at the Golden Rule Service Station. Laura died from a heart condition in December 1941, at age 66. After Laura died, Milford moved back to Fellsmere where his sister, Lillian Weigle; his son, Ellsworth; and daughter, Mrs. Mary Weigle Pennington, lived. Eventually, Milford had to go to a nursing home in Vero Beach, Florida, where he died on July 1, 1964, at age 90. He is buried in the Vero Beach Crestlawn Cemetery.17

Ellsworth Weigle was born on April 19, 1899, in Merlin, Canada.18 He moved to Fellsmere with his parents, brothers George and Dewitt, and sisters Mary Beatrice and Wilhelmina in 1917, when he was 18 years old.19 His father, Milford, taught Ellsworth everything he needed to know about repairing cars while working in the family garage at the house in Fellsmere between 1920 and 1925.

Ellsworth married Anna Green on June 4, 1921.20 They originally lived in a house known as “Pinehurst” on North Cypress Street and moved in October 1921.21 They moved into the house at 120 North Oleander Street (aka the R. E. Brown house). It was the third house from the corner of New York Avenue and North Oleander Street and is still there today but is a private residence and not open to the public.22

The property on which the Fellsmere Garage was built (initially Lots 17 and 18, Block 99, in the Town of Fellsmere) was owned by Theodore and Emma Gilchrist of Washington County, New York, in the 1920s.23

In 1925, Ellsworth leased the property from the Gilchrists and opened the Fellsmere Garage on North Broadway.24 However, he did not own the building until five years later after the property changed ownership several times. The Gilchrists sold the property to Rosa B. Sloan of Indian River County, Florida, on July 13, 1927.25 A little more than three years later, Rosa and her husband, L. A. Sloan, sold the property to N. N. Warren and R.W. Ling of Melbourne, Florida, on September 30, 1930.26 On October 2, 1930, only three (3) days after the property was sold to Warren and Ling, they in turn sold the property to Ellsworth and his wife Anna Weigle of Fellsmere, Florida.27

On October 3, 1930, one day after Ellsworth and Anna purchased the property, they entered into an agreement to lease the land to The Texas Company (later named “Texaco”) for two years. The Texas Company agreed to pay one cent for each gallon of gasoline sold on the premises, and to maintain the premises. A gasoline pump was then installed in front of the Fellsmere Garage between the sidewalk and the curb along Broadway.28

On September 13, 1935, Ellsworth asked the Fellsmere City Council for a permit to repair his building and to build a gasoline station. Council granted his request, and a permit was issued that was good for one year.29

During the time Ellsworth Weigle was repairing vehicles in his garage, he became very active in city politics. On February 7, 1936, he was sworn in as a Fellsmere City Councilman by Mayor H. C. Watts, who then appointed him to the Finance Committee.30 Two years later he ran for office again and was elected for another two-year term as Councilman on February 11, 1938.31 Weigle had to resign 14 months later on April 14, 1939, because he had moved outside the Fellsmere city limits. Although his resignation was accepted by the Council, they approved him to become the Maintenance Manager of the City’s streets and bridges at a salary of $1.00, until February 1940.32

Ellsworth and Anna Weigle moved to a spacious home on Tract 1331 that they purchased from Grace Rosenke on July 29, 1939.33 The property consisted of 9.84 acres of property at 10055 County Road 507 (138th Avenue fka North Road) at the southwest corner of 101st Street (Ditch 12).34 The house was reportedly built in 1920. Ellsworth’s daughter, Barbara Robinson, said that at the time, it was a three-bedroom house with a sewing room, living room, dining room, sun parlor, kitchen, dinette, one bathroom, and a screened-in porch. It was a spacious house for its day.35

In addition to being the Maintenance Manager of the City’s streets and bridges, Ellsworth Weigle was appointed as Alternate Fire Chief by action of the Fellsmere City Council on September 22, 1939, but did not receive any compensation as the fire department was comprised of all volunteers.36

After Ellsworth’s term as Maintenance Manager of the City’s streets and bridges expired in February 1940, the Fellsmere City Council again approved of Ellsworth Weigle on May 10, 1940, to take over supervision of municipal work for a token amount of $1.00 per year. There were only two city employees at the time, City Clerk Ed Seegers and Street Maintenance Man J.D. Spivey. The total City of Fellsmere payroll was $74 per month, so Ellsworth basically volunteered his services to the City.37

At the November 13, 1942, City Council meeting, City Clerk Seegers read the resignation of Ellsworth Weigle as “City Manager and Garbage Collector”.38 Weigle was 43 years old at the time. After he resigned, Ellsworth Weigle never again served in any capacity for the City of Fellsmere.

Ellsworth contracted pleurisy from working under the cars while lying on the cold concrete floor. He had also lost the vision in one eye while working on cars. He never used goggles or any eye protection even after that the loss of his eye. He used two different glass eyes, one green and one blue. Unfortunately, he developed glaucoma in his one good eye. For some time after closing his garage, Ellsworth grew gladiolas and Easter lilies, and raised cattle on his property. Later, he went to work at the Fellsmere Sugar Mill as an electrician on the second shift (3 p.m.-11 p.m.) until he retired in 1965. He died on August 27, 1985, at age 86, and is buried in the Vero Beach Crestlawn Cemetery.39

On January 5, 1945, the Weigles sold the Fellsmere Garage to Walter Newlan and Barney Stokes of Indian River County.40 A year and a half later, on June 24, 1946, the property was sold by L. D. and Lucinda Hogan of Fellsmere to John Horschel of Fellsmere.41 No record was found as to when Newland and Stokes sold the property to the Hogans.

Less than a year later, John Horschel, and his wife, Kathryn, sold the property to T. J. and Lela McMillan of Fellsmere on March 17, 1947.42 The following year, on June 4, 1948, the McMillans sold the property to Gilbert and Grace Barkoskie of Fellsmere.43 However, T.J. McMillen continued to operate the garage.44

Gilbert Barkoskie had worked for the Fellsmere Farms Company during the early days of Fellsmere and raised cattle as a rancher. He started with 50 head of cattle in 1916 and grew the herd to more than 2000 head of cattle. He also served on the Indian River County School Board and on the County Commission. He served as a State Director of the Florida Cattlemen’s Association and several terms as President of the Indian River Cattleman’s Association. Shortly before his death in 1983, he was named as the “Cattleman of the Century”.45

Gilbert Barkoskie owned the Fellsmere Garage property for 10 years and sold it to Frank Foots, a local mechanic, on October 29, 1958.46 Frank died in 1964, Sarah Foots, his widow, and son, Frank L. Foots, Jr., sold the property to Stanley and Faye Lawrence of Fellsmere on December 26, 1970.47 The Lawrence’s had the property for less than a year when they sold it to David and Cynthia Hines of Fellsmere on October 6, 1971.48 The Hines sold the property in the following year to Clarence McKinley Ballard of Melbourne, Florida on December 29, 1972.49 Clarence, in turn, sold the property to McKinley Cole Ballard of Fellsmere on January 22, 1974.50

Clarence held the property for four (4) years and then sold it to Raymond Rancourt and Gregory Lehman of Fellsmere (each having an undivided half interest) on May 14, 1976.51 A year later, on May 20, 1977, Lehman sold his interest to Rancourt.52

Sometime after May 20, 1977, Rancourt deeded the property to William R. and Dorothea Rowland of Sebastian. On October 27, 1980, William C. and Helen Bartram conveyed Lot 16, Block 99 to the Rowlands.53 After 16 years, the Rowlands sold the property to Joe Driver of Roseland on December 31, 1996.54

On July 6, 2005, Joe and Beverly Driver sold the Lots 16, 17, 18, and 19, Block 99, to Jerald and Laura Smith of Fellsmere.55 Then on June 24, 2006, the Smiths sold Lots 14-19, Block 99, to Santosh International, Inc. of Merritt Island, Florida which is the present owner as of this writing.56 Over the past 100 years, the property has changed owners many times since being initially owned by the Fellsmere Farms Company which recorded the plat of the Town of Fellsmere on July 31, 1911, in the public records of St. Lucie County.57

It is not certain when the Fellsmere Garage ceased to repair vehicles and sell gasoline. According to longtime resident of Fellsmere, Barbara Weigle Robinson, daughter of Ellsworth and Anna Weigle, the Fellsmere Garage was used to store vehicles when it ceased operations as an automobile repair shop.58 As late as 1995, the “Fellsmere Garage” sign was visible over the old wooden garage door in the front of the building. Prior to 1995, the building was vacant for many years until the late 1990s when it was remodeled. The building was converted into the Lucky Strike Bar and Grill, then Club Anthrax, later the Broken Spoke Bar and Grill. As of November 1, 2020, the building was renamed Willy’s Bar and Grill and is leased and managed by Adam Morris.

Barbara Weigle Robinson was born on August 15, 1936, in the first Indian River Hospital (a hotel located on Old Dixie Highway) in Vero Beach. This was the original hospital in Vero Beach established by Garnett Lundsford Radin in 1932. Eventually, this hospital was the forerunner of the Indian River Medical Center.59

Barbara Weigle (Robinson) was raised in Fellsmere and attended all 12 grades at the Fellsmere Public School (now Fellsmere City Hall) at 22 South Orange Street. She graduated in 1954 in a class of six. Barbara was a long-time member of the Fellsmere Community Bible Church (originally known as the Fellsmere Union Church, built in 1913), the oldest church in Fellsmere. Robert Green helped to build the church, and he and his two older sons did much of the painting. Barbara is related to Robert Green because Milford Weigle, Barbara’s grandfather, married Robert Green’s sister, Laura. In turn, Robert Green married Milford Weigle’s sister, Maude. Therefore, Barbara is related to both a builder of the Fellsmere (Union) Community Bible Church, the oldest church in Fellsmere, and the Fellsmere Methodist-Episcopal Church, the second oldest church in Fellsmere.60 Her grandfather, Milford, was the first choir director of the Fellsmere Methodist-Episcopal Church, and the individual responsible for getting the bell that is still located in the church’s bell tower.61

Every March from 1994 to 2018, Barbara organized and hosted the Fellsmere Old Timer’s Reunion for old time Fellsmere residents to get together and share memories about the good ole’ days. After Barbara no longer hosted the reunion, others held it for a few years but reunions ceased for the final time in 2023 for lack of attendance.

In 2016, Barbara moved to Sebastian from Fellsmere after her husband, Elmer “Robbie” Robinson, passed away. As a pure coincidence, Barbara’s husband, Robbie, had lived in Newcastle, Indiana, where her grandparents, the Weigles, had lived before coming to Fellsmere in 1917.

Barbara has a comprehensive knowledge of Fellsmere having been born and raised there and has always been a valuable source of information concerning the history of Fellsmere. Most significantly, she provided a wealth of information about her grandfather, Milford Weigle, and the First Transcontinental Automobile Race in 1905 that he and Dwight Huss won more than a century ago.

The following is the American History Magazine article from its June 12, 2006 Edition repeated in its entirety:

“THE FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL CAR RACE CROSSED THE OREGON TRAIL”

“Sixty years after the first great columns of prairie schooners lumbered along the Oregon Trail, two tiny and primitive automobiles followed the historic ruts across the West. The year was 1905, and the cars were in the first transcontinental automobile race.

The pair of 7-horsepower Curved Dash (so called because of the sleighlike front of the body) Olds Runabouts made their historic journey from New York City to Portland, Ore. Essentially motorized buckboards, these were the first automobiles negotiating the Oregon Trail, first to cross the United States from east to west and the first over the Cascade Range. Although parts of the United States were quite ‘civilized,’ in 1905, the 20th century was only a spotty veneer over the western United States. The little cars and their drivers faced bad weather, sickness, wild animals, thirst, accidents and unforeseen breakdowns. Crossing the Oregon Trail was still a rough trip.

The automobile was a growing presence in larger cities and even in some towns. Endurance races and tours were popular events. The densely settled Eastern states had a network of established roads, some of which even had graveled surfaces, but most were little more than smoothed-out trails. There were less than 150 miles of hard-surface roads in the entire country, all of it in cities.

The race was a publicity event as well as a contest. The first prize was a very respectable (particularly in those days) one thousand dollars. James W. Abbott, a major organizer of the race, wrote: ‘[The] important purpose was to bring vividly to public attention a clearer knowledge about all phases of existing transcontinental highways.’

Abbott worked for the Department of Public Roads in the Department of Agriculture. Together with Olds Motor Works and a group called The National Good Roads Association (a group of bicyclists who acted as the first highway lobby), he published an advertisement for entrants in the race, called ‘From Hell Gate to Portland.’ The Association’s 5th annual convention was to be held at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland on June 21, 1905.

The race began auspiciously in New York City on May 8, with fanfare and good weather. One of the cars, Old Scout was even cautioned for speeding. Everyone was optimistic. But, like so many earlier westbound emigrants, these pioneers found the trip much harder than expected. Organizers had estimated the trip would take 30 days. They were wrong.

The cars were single-cylinder, tiller-steered, chain-driven and water-cooled. Old Scout was driven by Dwight Russ, an employee of Olds and an accomplished driver. His mechanic and co-driver was Milford Wigle {Weigle}, also of Detroit. The other Runabout, Old Steady, was driven by Percy Megargel and Barton Stanchfield. Both Megargel and Huss had driven in tours and races. Huss had raced also in England and Europe, accumulating an impressive record of victories. Only 13 years after the first American car-the Duryea-was built, Americans were racing at home and abroad.

The previous year, a 90-pound ‘motor-bicycle’ had crossed the continent from west to east, following (and often riding on) the tracks of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads. But driving a race over the Oregon Trail turned out to be a much greater challenge than riding a motorized bicycle.

For the race’s organizers, a snow-free crossing of the Cascades was considered the most important factor. They had not considered the unpredictability of spring weather. Three days into the trip, rain began and continued for half of the race. It rained every day for three weeks. Miles and miles of the route became lakes and swamps. Dwight Huss wrote of following roads that were completely under water, and he steered by keeping parallel to the telegraph poles.

For the next 1,000 miles, there was mud and rain, more mud and more rain. Each state seemed to outdo the one before in quantities and qualities of mud. Downpours seemed endless. The spoked wheels were so packed with mud they appeared solid. To save weight, the cars carried neither fenders nor tops. The drivers were as muddy and wet as their machines. One of the most useful tools they each carried was a block and tackle.

They crossed the Missouri at historic Council Bluffs, Iowa, the major jumping-off point for earlier pioneers. Eastern civilization was left behind. From Nebraska on, the two cars were on a journey under conditions not that different from half a century before. The racers had neither road maps nor gas stations. The only guidebooks were those written for the pioneers crossing the Oregon and California trails, 50 years before. Conditions got worse. Only trails and tracks crossed the wilderness.

Herds of animals blocked the route across the prairies. Instead of the vast throngs of buffalo encountered by the wagon trains, these were cattle and hogs. The drivers nudged their way through and continued.

Because of supply logistics, the route followed the Oregon Trail as the Union Pacific followed the trail. Ruts from iron-tired wagons were the nearest things to interstate highways. At Julesburg, Colo., the cars turned northwest into Wyoming. They reached Cheyenne 11 days behind schedule.

Old Scout took an early lead and held onto it. The two Runabouts began meeting numerous covered wagons still using the trail. As one participant wrote: ‘We passed many parties of traveling prairie schooners to and from the east. These schooners, usually a single wagon drawn by two or four horses, or mules, with one or two saddle ponies and a cow tied behind, are visible for miles, their big white canvas bow tops glistening in the sunshine, and we often pass as many as half a dozen of them traveling together.’

The race was a well-publicized and popular event for the lonely settlers. Townspeople, ranchers, cowboys and sodbusters rode for miles to see the Runabouts pass through their country. People were interested not in the sport of the race, however, but in the utility value of the machines. They wanted to know if automobiles were practical in the rugged West. Horses bucked and kicked as the cars chugged by. The riders laughed and stayed on their bucking mounts. They shouted at the drivers, ‘Good luck boys, give ’em hell!’

The drivers didn’t give ’em hell’-they got it. Navigating through the gumbo, Huss wrote, the cars carried a half-ton of mud. That nearly doubled the little cars’ weights. (A popular joke of the time claimed that the cars sold for a dollar a pound-650 pounds for $650.) Two hundred pounds of tools and fuel were carried as well. The cars were packed to double their weight, counting the mud. Driver and mechanic added another three hundred pounds-7 hp to move nearly a ton. Surprisingly, on good stretches, the cars could actually speed along at 15 miles an hour!

There weren’t a lot of good stretches, however. Huss wrote of one day in Wyoming, ‘we drove 18 hours, forded five streams and made a total of 11 miles.’

Where the trail had dried, the ruts were so deep and numerous the cars couldn’t stay out of them. Their axles high-centered between the ruts, forcing the drivers to dig out with shovels. They often had to back up half a mile to a place where they could steer onto relatively smooth ground. But soon, Huss said, they would end up high-centered once again. Iron-hard clay cut the tires to shreds. Rocky stretches were worse. One set of tires was worn out every 90 miles. Huss said he had no idea how many tires were destroyed on the trip.

Supplies, for the most part, were not a problem. Abbott arranged supply depots along the course. While gasoline was generally available, at least in small quantities (in drug stores, for dry cleaning), larger amounts had been stockpiled in advance by train and stagecoach. Stocks of oil, tires and batteries had also been arranged. The cars did not have magnetos. Instead, the engine spark was produced by dry-cell batteries, with a limited lifespan. Deep water would short out the batteries and the engines would die.

Surprisingly, the cars could still run with water over the axles. But not always. More than once, water splashed into the carburetors and killed the engines. Once on dry land, the men opened petcocks on the blocks and cranked the engine-by hand, of course-until all the water was expelled. At one point, Old Steady was topped off with the wrong kind of engine oil; the combination caked and seized the engine. Megargel had to walk to the nearest settlement, hire a team, and tow the car back into town. Gasoline, kerosene and lye were tried; nothing freed the piston. After laboring all night, they discovered that only muriatic acid would cut the resulting varnish.

Farmers and ranchers had arbitrarily fenced off portions of the route. The drivers cut the fences and kept on going. At Omaha, the drivers purchased side-arms and then wore them on their hips, as did most of the people they encountered in the West. Law was still distant, arbitrary and personal. Fortunately, all they ever felt motivated to shoot were rabbits and rattlesnakes. Huss used his pistol for hunting, so they could obtain fresh meat. Eggs and pork were the usual diet.

The cars proved remarkably durable. Despite their flimsy appearance-they were of much lighter construction than the covered wagons or even farm wagons of the time-they endured terrible punishment. The radiators were mounted underneath, between the axles, and took a constant beating. Rocks, mud and sagebrush clogged the cooling fins. As the popular song went, the men would have to ‘get out and get under.’ Using screwdrivers and knives, they picked debris out of the fins. Endless miles of sagebrush jammed the drive chains, causing the gears to bind and lock up the rear axle. Again, the drivers and mechanics got out and under. Huss laconically commented that if Old Scout could have lived on sagebrush they never would have finished.

Because of difficulties and delays, the men had to drive at night. The headlights, inadequate at best, were powered by acetylene. Searchlights had been mounted for night driving, but they also used acetylene. That was the one item in short supply. With or without lights, accidents happened. Old Scout fell into a badger hole and severely damaged the front axle. A reluctant blacksmith (Huss bribed him $10 dollars to work at night) made repairs that lasted the rest of the trip. Many field repairs were extremely creative, but they worked. The simplicity of the cars and the resourcefulness of the drivers were the secrets of their success.

They followed the historic route up the Platte and the Sweetwater, and along the trail over the Continental Divide at South Pass. Now they were onto the Pacific side of the country. Following the ruts, they encountered snow that caused Megargel and Stanchfield, in Old Steady, to become temporarily lost. Stanchfield got altitude sickness. Megargel found a doctor, who also demanded an extra $10 fee. Even 90 years ago the automobilist was seen as ‘an easy mark.’ Banditry took a new, more modern, turn.

They encountered herds of antelopes, and chugged through miles of prairie dog towns. One participant wrote: ‘…about every five miles we would strike one of these dog villages, comprised of from two to five hundred mounds. The dogs would congregate on the tops of their houses until Old Steady would be almost upon them, when they would scamper down into the regions below.’

Bands of wild horses were attracted by the noise and motion of the cars. The horses would form a crescent in front and to the sides of the cars and run with them for miles and miles.

Rattlesnakes attempted to ambush the cars and breakdowns occurred in the middle of nowhere. Mud became less of a problem, although Huss remarked that the western states didn’t believe in building bridges. Most existing bridges had been washed out by the spring rains. Old Steady, driving with inadequate lights at night, crashed into a broken bridge and bent both axles. No matter: They hastily pounded the axles back into a simulation of straightness and continued. Some swollen rivers were too much for a block and tackle. After one storm, Old Steady was engulfed in a raging stream:

‘We half waded and half swam to the shore, leaving the car with just the top of the seat above water. … Sighting a sheep ranch in the distance, we walked to it. Eventually we found the owner, Lone John, in the barn….He was at war with several of his neighbors, and kept a loaded gun at hand at all times. He had just been released for cutting open the head of one of his neighbors with an axe, and he regretted the fact that he had not killed the man. Despite his grievances, he willingly threw the harness on his horses, and telling us where we would find the wagon, and to use his team as we saw fit. … We drove the bronchos [sic] down to our stranded machine, and, attaching a line, soon pulled it out of that creek, and through four others before we got to the ranch.’

Later the men suffered from the lack of water. Huss went for several days without drinking water and became disoriented. Attempting to cross Idaho’s Snake River Plain, the cars bogged down in sand dunes. The drivers mounted specially made, wide-treaded ’sand tires’ and kept heading west.

Here, finally, the racers encountered their first Indians, friendly Shoshonis from Fort Hall Reservation (many of whom were later hired for the first epic film about the Oregon Trail, The Covered Wagon). Like the covered wagon emigrants, the drivers reflected the same cultural biases. Megargel complained that ‘the man stealing the most is regarded as the bravest.’ The Shoshonis operated a primitive towing service. They kept teams of horses available to pull-for a fee-hapless wagons out of the sand dunes in the area. The Runabouts, though, with their special sand tires, didn’t need the help. This delighted the drivers and annoyed the Indians. In eastern Oregon, some native people refused to have their pictures taken with the evil-smelling, noisy machines. Perhaps the Indians somehow saw the future and really didn’t want any part of it.

Crossing the Cascade Range was the hardest part of a hard trip. The road over Santiam Pass had originally been a military road, opened to allow supplies and troops to move back and forth during the period of Indian resistance to white settlement. After the resistance was crushed, it became a toll road. Santiam Pass was considered one of the easier passes through the mountains. Easy, however, turned out to be a relative term. What is easy for a freight team, or a rider on horseback, is not necessarily easy for an automobile.

The crossing began with jokes. At the Cache Creek toll gate, on the east side of the pass, the drivers and gatekeeper squabbled over the toll rates. Eight-horse teams were charged $4, and six-horse teams cost $3-but hogs went for 3 cents a head. Since teamsters had called the cars ‘roadhogs,’ the drivers argued they were entitled to passage at 3 cents a head. But a telegram arrived from the road company, instructing the toll collector to let them pass for free. It made for good publicity.

Huss described the road as being ‘paved with boulders.’ Time and time again, they had to pile rocks to allow the cars’ small wheels to negotiate giant rocks. Portions of the ascent were simply too steep for the heavily laden little cars. The blocks and tackles came out again.

The descent was terrifying. The brakes on the Runabouts were little better than the ones on covered wagons. Like the pioneers, trees were cut and dragged behind, to add braking power. Huss’ mechanic, Wigle, rode the tree down to increase the drag. Old Scout slid close to disaster, and at one point had both left wheels hanging out in space.

Several days later, Old Steady came even closer to destruction: the car went into a four-wheel slide. Megargel wrote: ‘you have no idea of the sensation of a skid, down a fifty per cent grade in the Cascade mountains, thirty miles from the nearest house. Down, down, we came … ‘ Finally Old Steady tossed out the driver and co-driver, and came to rest hanging over a precipice. A prairie schooner came along and hauled the little runabout back onto the trail. This may well be the only time an automobile was ever rescued by a covered wagon.

Eventually, Old Scout made it to Portland only an hour before the opening of the convention. The trip had been figured at taking a month; it took half again that long-44 days. Megargel and Stanchfield were eight days behind. Having decided they has already lost, the two men finished the race in a leisurely fashion, stopping to fish and loaf. Their reception in Portland was not much less than that accorded to Huss. Haberdashers gave them new clothes in exchange for displaying their worn garments in shop windows. Megargel ended his account with: ‘I am commencing to believe that possibly I do belong to the freak family, a belief strengthened by the numerous mailing cards sent me, usually containing in bright letters of scarlet, ‘It’s great to be crazy and ride around in an automobile.”

Later in the year, Megargel repeated the trip; this time he went south from Portland, into California, and then east again. He is credited with being the first person to cross the Mojave Desert in an automobile, as well as the first to cross Arizona. Pioneer automobilists, and trailblazers, these early drivers made America aware of the need for decent all-weather roads across the nation.

Huss, though, reflected a less optimistic sentiment. In an interview for Life magazine in the mid-1950s, he said: ‘The truth is, we’d all be better off if we never had any danged automobiles at all …”

NOTE: The American History magazine can be found online and is published quarterly.